For information on accessing documents, see note at the end of this post.

Even after three days of testimony by Jeffery Gentry, the man in charge of science and operations at RJR Tobacco, I still can't figure out whether any of his remarks were relevant to the Montreal tobacco trials. It's even hard to guess how they might be helpful to JTI-Macdonald Tobacco, which asked him to testify in their defence.

It would be a major trial development if Justice Riordan opened the door to recent events in foreign countries by non parties. For the first 18 months, these proceedings were firmly locked in time, with the bolt sealed in 1998, the year that the suits were first filed.

But even if he did, much of what Mr. Gentry said only helps the plaintiffs establish that the company which once sold Export A cigarettes in Canada:

* sold a product they knew to be dangerous ("Cigarettes are dangerous, they've always been inherently dangerous")

* downplayed the dangers of their products ("We maintained that it represented a risk or could be hazardous. We did not come out until the early 2000s and say it caused disease.")

* sold a product they knew to be addictive ("Nicotine in tobacco products is addictive.")

Mr. Gentry's company is not involved in this suit or in Canada and will face no direct penalties from any result. Nonetheless, his comments this week don't seem to advance their cause either. My American colleagues will doubtless find much to reflect on in the transcript of his testimony on the fifth, sixth and seventh of November, and especially his framing of the responsibility to make cigarettes less harmful.

Yet it was an interesting week -- fun to watch and, I think, an exciting one for the lawyers involved. I doubt the plaintiffs ever anticipated they would be able to question a senior executive from a large American tobacco company. They were clearly enjoying the new terrain that Mr. Gentry offered, as well as the professional challenge of making such a skilled opponent's witness work to their advantage.

First, the paperwork

The unflappable Pierre Boivin took the first crack at cross-examination yesterday afternoon, and he did so in his usual understated and anti-theatrical way.

He followed his practice of limiting questions and giving himself generous pauses to order his thoughts and papers. In this style he encouraged Mr. Gentry to make a few key admissions in simple sentences, and he put several damaging documents on the record.

Low tar for health? or High tar for addicts?

Mr. Gentry had testified that attempts to increase the amount of nicotine relative to tar in cigarettes were an initiative to make cigarettes less harmful, and that this work was spurred by the recommendations of the 1980 Banbury report. (Exhibit 20053.1)

Mr. Boivin pointed out that long before this time, Claude Teague (who became director of Research at RJR until l987) anticipated the need to increase the nicotine per tar ratio because "for the typical smoker nicotine satisfaction is the dominant desire, as opposed to flavor and other satisfactions." (Exhibit 1624).

Well before Michael Russell or others encouraged increasing nicotine in low tar cigarettes, RJR was trying to make this happen. Their "top priority" was to product products which would "maximise the physiological satisfaction per puff - the single most important need of smokers." (Exhibit 1625)

A class 2B act.

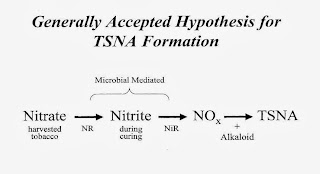

Mr. Trudel took over the cross examination this morning, and kept Mr. Gentry moving back and forth on a handful of topics over the day. Many of these were linked to the levels of Tobacco Specific Nitrosamines, or TSNAs. (These compounds mean what they say, they are principally found in tobacco).

He maintained an affable and almost friendly tone, but this did not disguise his intent to chip away at the impression left by Mr. Pratte that RJR had played a constructive role in the changes to the curing system that was intended to reduce TSNAs, including in Canadian cigarettes.

To begin with, there was the question of how dangerous, exactly, TSNAs were.

Mr. Gentry initially would not admit that they were a known human carcinogen. "They are a Class 2B - possible human carcinogen" he had testified, referring to the IARC ranking.

Even when Mr. Trudel suggested that the IARC classification might be the higher Class 1 "known human carcinogen" category, Mr. Gentry would not agree. "No. They are Class 2B."

Justice Riordan invited Mr Trudel to resolve the question. "If you want to go argue about whether they're Class 1 or Class 2, we can do that." In an argument over a simple scientific fact, Mr. Gentry might have been expected to have the upper edge. He was, after all, the one with an advanced science degree and the one had been working for decades in the only industry whose products contain these compounds.

His own lawyer, Mr. Pratte, was also encouraging. "Why wouldn't we get the answer now?" Earlier in the week he had invited Mr. Gentry to comment on RJR's knowledge of the cancer causing chemicals in cigarette smoke, and had introduced the company's research in this area. (Exhibit 40354.1, 401354.2, 40354.3). He might be forgiven for thinking his witness was on solid footing.

Others might have forgotten, but Mr. Trudel had his hands on a more current report from IARC that was presented by his own expert witness in toxicology. (Exhibit 1440). This list showed that indeed TSNAs were Class 1 carcinogens.

"You are correct," Mr. Gentry admitted, as Justice Riordan took notes. Mr. Pratte sat stone-faced.

Ignored for a quarter century

Mr. Gentry had said that the company acted to reduce nitrosamines as soon as possible. Mr. Trudel wanted to know why they waited 25 years after learning how to measure TSNAs before routinely testing for them. Mr. Gentry confirmed that the technology had always been available but that no one had thought to do so.

"Nobody thought of it before then?

"No, I'm sorry we didn't. And no one did. When Dr. Peele and I first discussed it, it was, "This can't possibly be it.... it was shocking.... No one knew to look here, including prominent public health researchers like Dr. Hoffmann."

But was it really RJR that made the discovery that TSNAs could be reduced by changing the way tobacco was cured? Mr. Trudel had documents that suggested otherwise.

When testifying on his 1999 research paper on nitrosamines (Exhibit 40368) Mr. Gentry had made no reference to a visit to he made to the Star Tobacco company in early 1997. There he had observed curing methods that reduced nitrosamines (Exhibit 1627). Nor had he mentioned that the he was aware that Star Tobacco was changing the heating system in some curing barns. (Exhibit 1629, 40369).

I may have been the only one not in on the joke as Mr. Guy Pratte intervened to stop further questions about RJR taking credit for someone else's work. "I really don't see the relevance of this, unless my friend wants to sue for patent violation."

Justice Riordan agreed. "Do you have a side patent violation practice, Maitre Trudel?" he asked before cautioning 'We're not going to get into an argument between Star and R.J. Reynolds, are we?"

So, officially the court was never informed that there was indeed a patent fight between Star and RJReynolds over who owned the discovery. (A settlement was reached in 2012). I only learned about it during the break, as I Googled to find out why Mr. Pratte had chosen to defend his witness in this way.

Selling poisons to consumers

The reduced-TSNA story was beginning to look quite battered even before Mr. Trudel introduced RJR's own recap of the program. (Exhibit 1630).

It was only when seeing this document that Mr. Gentry acknowledged that their own tests had shown that "the reduction in TSNAs did not reduce the toxicity of the product."

Justice Riordan would not allow the "poison" button to be pushed again. "It’s a pointless exercise to ask these people 'do you admit you're selling poison'. It is harassment if it goes too far."

As safe as possible.

Mr. Gentry had spent much of his first days of testimony talking about his work in designing less harmful cigarettes that were not marketed, but did not seem to think this work was logically connected to the conclusion that those products which remained on the market were not as safe as they might have been. Both Mr. Boivin and Mr. Trudel explored this theme.

"Is it your testimony today, Doctor, that Reynolds manufactures and sold cigarettes that are as safe as possible?"

"Yes. I believe that we've always tried to make our product as safe as possible. Cigarettes are inherently dangerous. They've always been inherently dangerous. But I believe we've tried to make them as safe as we possibly could. "

When asked how both a low tar and high tar cigarette could be as safe as possible, given that Mr. Gentry believed the low tar cigarette to be "safer" he explained "both of them are different, and consumers choose different products. So we offer the range of products, but both are as safe as we can make the corresponding products." No risk of paper cuts when opening the box of bullets?

Mr. Gentry, like his BAT colleague Mr. Dixon, continues to have faith in the low-tar strategy. He cited the studies reviewed by Monograph 13 to disagree with the conclusion of that scientific consensus process. "All of the epidemiology studies that Monograph 13 was built off of, over time, did show reductions in tar, did show that there was reasons to believe that reducing tar would be a way to reduce risk."

Mr. Trudel wanted to know why, if the company thought that low tar cigarettes are less harmful, it did not share this information with their customers. "We believe that reducing tar exposure will reduce the risk for smokers, and we don't publicly debate that. We defer anyone who's concerned about smoking and health to the public health; we don't debate that in public. We'll talk about it in a courtroom or things like that, but we don't debate that in public."

The unwillingness of consumers to accept less harmful products was the reason repeatedly given for the withdrawal of less hazardous products from the market. "At the end of the day, consumer acceptance is the thing that makes the difference, because if someone won't buy your product, I don't care how safe it is, it has done no one any good. It hasn't done public health any good; it hasn't done the manufacturer any good. Consumer acceptance is critical."

Mr. Trudel wanted to know why more was not done to encourage smokers to try such products. "Without the science, we cannot do that," said Mr. Gentry, referring to epidemiological studies that would require people to have used such products for a period of years. "It's a circular argument."

Mr. Gentry was asked about the bigger picture for harm reduction. "Today, their [RJR] strategy is much more encompassing along the concept of harm reduction, to actually offer additional other products, aside from cigarettes, that contain nicotine but are much safer to use, such as smokeless tobacco, e-type cigarettes, NRTs."

Weaving throughout the day was the issue of RJR Tobacco's "stewardship philosophy" which Mr. Gentry explained was "very simple - We will not do anything to our products or add anything to our products that increase the inherent risk."

To access trial documents linked to this site:

The documents are on the web-site maintained by the Plaintiff's lawyers. To access them, it is necessary to gain entry to the web-site. Fortunately, this is easy to do.

Step 1: Click on: https://tobacco.asp.visard.ca

Step 2: Click on the blue bar on the splash-page "Acces direct a l'information/direct access to information" You will then be taken to the document data base.

Step 3: Return to this blog - and click on any links.

It would be a major trial development if Justice Riordan opened the door to recent events in foreign countries by non parties. For the first 18 months, these proceedings were firmly locked in time, with the bolt sealed in 1998, the year that the suits were first filed.

But even if he did, much of what Mr. Gentry said only helps the plaintiffs establish that the company which once sold Export A cigarettes in Canada:

* sold a product they knew to be dangerous ("Cigarettes are dangerous, they've always been inherently dangerous")

* downplayed the dangers of their products ("We maintained that it represented a risk or could be hazardous. We did not come out until the early 2000s and say it caused disease.")

* sold a product they knew to be addictive ("Nicotine in tobacco products is addictive.")

Mr. Gentry's company is not involved in this suit or in Canada and will face no direct penalties from any result. Nonetheless, his comments this week don't seem to advance their cause either. My American colleagues will doubtless find much to reflect on in the transcript of his testimony on the fifth, sixth and seventh of November, and especially his framing of the responsibility to make cigarettes less harmful.

Yet it was an interesting week -- fun to watch and, I think, an exciting one for the lawyers involved. I doubt the plaintiffs ever anticipated they would be able to question a senior executive from a large American tobacco company. They were clearly enjoying the new terrain that Mr. Gentry offered, as well as the professional challenge of making such a skilled opponent's witness work to their advantage.

First, the paperwork

The unflappable Pierre Boivin took the first crack at cross-examination yesterday afternoon, and he did so in his usual understated and anti-theatrical way.

He followed his practice of limiting questions and giving himself generous pauses to order his thoughts and papers. In this style he encouraged Mr. Gentry to make a few key admissions in simple sentences, and he put several damaging documents on the record.

Mr. Congressman, cigarettes and nicotine clearly do not meet the classic definition of addiction.

One of the seminal moments in modern public health history was the April 1994 appearance of seven CEO's of American tobacco companies before the Congressional sub committee looking into tobacco regulation. By connecting Mr. Gentry to this event, Mr. Boivin was able to make it something that Justice Riordan is allowed to consider when making his judgment.

Mr. Gentry was a staff chemist when this hearing took place. But he was not shy to reach up and, as the Chinese say, pat the horse. "Whether you realize it or not, your dominance of the sub-committee hearings made all RJR employees very proud," he wrote in an almost gushing letter to his CEO, James Johnston. (Exhibit 1623)

This letter was the technical hook needed to convert Mr. Johnston's comments at that infamous hearing into a trial exhibit. (Exhibit 1623.1) Among those were many which denied or trivialized addiction. But whereas similar testimony before Canada's Parliament is tangled up in arguments about parliamentary privilege, there are no such constraints on statements made to foreign legislatures.

It was Mr. Pratte who opened the door to U.S. testimony and it was Mr. Pratte who asked his witnesses to testify that during the 1990s all smoking and health issues were managed by RJReynolds. Without this, he might have been more successful in his objections to this record being filed. But if he realized as he watched this record being logged as an exhibit that he had scored a goal on his own net, his face didn't show it.

One of the seminal moments in modern public health history was the April 1994 appearance of seven CEO's of American tobacco companies before the Congressional sub committee looking into tobacco regulation. By connecting Mr. Gentry to this event, Mr. Boivin was able to make it something that Justice Riordan is allowed to consider when making his judgment.

|

| Seven doubters of the addictiveness of nicotine |

This letter was the technical hook needed to convert Mr. Johnston's comments at that infamous hearing into a trial exhibit. (Exhibit 1623.1) Among those were many which denied or trivialized addiction. But whereas similar testimony before Canada's Parliament is tangled up in arguments about parliamentary privilege, there are no such constraints on statements made to foreign legislatures.

It was Mr. Pratte who opened the door to U.S. testimony and it was Mr. Pratte who asked his witnesses to testify that during the 1990s all smoking and health issues were managed by RJReynolds. Without this, he might have been more successful in his objections to this record being filed. But if he realized as he watched this record being logged as an exhibit that he had scored a goal on his own net, his face didn't show it.

Low tar for health? or High tar for addicts?

Mr. Gentry had testified that attempts to increase the amount of nicotine relative to tar in cigarettes were an initiative to make cigarettes less harmful, and that this work was spurred by the recommendations of the 1980 Banbury report. (Exhibit 20053.1)

Mr. Boivin pointed out that long before this time, Claude Teague (who became director of Research at RJR until l987) anticipated the need to increase the nicotine per tar ratio because "for the typical smoker nicotine satisfaction is the dominant desire, as opposed to flavor and other satisfactions." (Exhibit 1624).

Well before Michael Russell or others encouraged increasing nicotine in low tar cigarettes, RJR was trying to make this happen. Their "top priority" was to product products which would "maximise the physiological satisfaction per puff - the single most important need of smokers." (Exhibit 1625)

A class 2B act.

Mr. Trudel took over the cross examination this morning, and kept Mr. Gentry moving back and forth on a handful of topics over the day. Many of these were linked to the levels of Tobacco Specific Nitrosamines, or TSNAs. (These compounds mean what they say, they are principally found in tobacco).

He maintained an affable and almost friendly tone, but this did not disguise his intent to chip away at the impression left by Mr. Pratte that RJR had played a constructive role in the changes to the curing system that was intended to reduce TSNAs, including in Canadian cigarettes.

To begin with, there was the question of how dangerous, exactly, TSNAs were.

Mr. Gentry initially would not admit that they were a known human carcinogen. "They are a Class 2B - possible human carcinogen" he had testified, referring to the IARC ranking.

Even when Mr. Trudel suggested that the IARC classification might be the higher Class 1 "known human carcinogen" category, Mr. Gentry would not agree. "No. They are Class 2B."

Justice Riordan invited Mr Trudel to resolve the question. "If you want to go argue about whether they're Class 1 or Class 2, we can do that." In an argument over a simple scientific fact, Mr. Gentry might have been expected to have the upper edge. He was, after all, the one with an advanced science degree and the one had been working for decades in the only industry whose products contain these compounds.

His own lawyer, Mr. Pratte, was also encouraging. "Why wouldn't we get the answer now?" Earlier in the week he had invited Mr. Gentry to comment on RJR's knowledge of the cancer causing chemicals in cigarette smoke, and had introduced the company's research in this area. (Exhibit 40354.1, 401354.2, 40354.3). He might be forgiven for thinking his witness was on solid footing.

Others might have forgotten, but Mr. Trudel had his hands on a more current report from IARC that was presented by his own expert witness in toxicology. (Exhibit 1440). This list showed that indeed TSNAs were Class 1 carcinogens.

"You are correct," Mr. Gentry admitted, as Justice Riordan took notes. Mr. Pratte sat stone-faced.

Ignored for a quarter century

Mr. Gentry had said that the company acted to reduce nitrosamines as soon as possible. Mr. Trudel wanted to know why they waited 25 years after learning how to measure TSNAs before routinely testing for them. Mr. Gentry confirmed that the technology had always been available but that no one had thought to do so.

|

| Nitrous oxides generate TSNAs Exhibit 1630 |

"No, I'm sorry we didn't. And no one did. When Dr. Peele and I first discussed it, it was, "This can't possibly be it.... it was shocking.... No one knew to look here, including prominent public health researchers like Dr. Hoffmann."

But was it really RJR that made the discovery that TSNAs could be reduced by changing the way tobacco was cured? Mr. Trudel had documents that suggested otherwise.

When testifying on his 1999 research paper on nitrosamines (Exhibit 40368) Mr. Gentry had made no reference to a visit to he made to the Star Tobacco company in early 1997. There he had observed curing methods that reduced nitrosamines (Exhibit 1627). Nor had he mentioned that the he was aware that Star Tobacco was changing the heating system in some curing barns. (Exhibit 1629, 40369).

I may have been the only one not in on the joke as Mr. Guy Pratte intervened to stop further questions about RJR taking credit for someone else's work. "I really don't see the relevance of this, unless my friend wants to sue for patent violation."

Justice Riordan agreed. "Do you have a side patent violation practice, Maitre Trudel?" he asked before cautioning 'We're not going to get into an argument between Star and R.J. Reynolds, are we?"

So, officially the court was never informed that there was indeed a patent fight between Star and RJReynolds over who owned the discovery. (A settlement was reached in 2012). I only learned about it during the break, as I Googled to find out why Mr. Pratte had chosen to defend his witness in this way.

Selling poisons to consumers

The reduced-TSNA story was beginning to look quite battered even before Mr. Trudel introduced RJR's own recap of the program. (Exhibit 1630).

It was only when seeing this document that Mr. Gentry acknowledged that their own tests had shown that "the reduction in TSNAs did not reduce the toxicity of the product."

And why not? RJR employees had been told that this was because "the poison is in the dose" - a reference to the foundation of toxicology and a suggestion, perhaps, that the smoke was so carcinogenic that such change made no difference. Today Mr. Gentry would not go that far. He said he "didn't know if this was the answer."

|

| Exhibit 1630 |

Mr. Trudel used this maxim to suggest that the "general reduction" in tar levels that he (and other industry witnesses) have claimed was of no benefit if the remaining dose of toxins received by smokers were enough to kill. Surprisingly, Mr. Gentry seemed to agree.

"If we put that in context with respect to general reduction, and seeing that general reduction does not show a reduction in mortality.. could we say that it's because the poison is in the dose?'

"Certainly. Anytime we're talking about cigarette exposure, or exposure to anything that could be cytotoxic, carcinogenic, it is a matter of how much."

"Is it okay to sell poisons to consumers?"

"We don't sell poison to consumers. We sell cigarettes to consumers, which are inherently dangerous. They contain thousands of chemicals, we don't dispute that. But we do not sell poison to our customers."

As safe as possible.

Mr. Gentry had spent much of his first days of testimony talking about his work in designing less harmful cigarettes that were not marketed, but did not seem to think this work was logically connected to the conclusion that those products which remained on the market were not as safe as they might have been. Both Mr. Boivin and Mr. Trudel explored this theme.

"Is it your testimony today, Doctor, that Reynolds manufactures and sold cigarettes that are as safe as possible?"

"Yes. I believe that we've always tried to make our product as safe as possible. Cigarettes are inherently dangerous. They've always been inherently dangerous. But I believe we've tried to make them as safe as we possibly could. "

When asked how both a low tar and high tar cigarette could be as safe as possible, given that Mr. Gentry believed the low tar cigarette to be "safer" he explained "both of them are different, and consumers choose different products. So we offer the range of products, but both are as safe as we can make the corresponding products." No risk of paper cuts when opening the box of bullets?

Mr. Gentry, like his BAT colleague Mr. Dixon, continues to have faith in the low-tar strategy. He cited the studies reviewed by Monograph 13 to disagree with the conclusion of that scientific consensus process. "All of the epidemiology studies that Monograph 13 was built off of, over time, did show reductions in tar, did show that there was reasons to believe that reducing tar would be a way to reduce risk."

Mr. Trudel wanted to know why, if the company thought that low tar cigarettes are less harmful, it did not share this information with their customers. "We believe that reducing tar exposure will reduce the risk for smokers, and we don't publicly debate that. We defer anyone who's concerned about smoking and health to the public health; we don't debate that in public. We'll talk about it in a courtroom or things like that, but we don't debate that in public."

The unwillingness of consumers to accept less harmful products was the reason repeatedly given for the withdrawal of less hazardous products from the market. "At the end of the day, consumer acceptance is the thing that makes the difference, because if someone won't buy your product, I don't care how safe it is, it has done no one any good. It hasn't done public health any good; it hasn't done the manufacturer any good. Consumer acceptance is critical."

Mr. Trudel wanted to know why more was not done to encourage smokers to try such products. "Without the science, we cannot do that," said Mr. Gentry, referring to epidemiological studies that would require people to have used such products for a period of years. "It's a circular argument."

Mr. Gentry was asked about the bigger picture for harm reduction. "Today, their [RJR] strategy is much more encompassing along the concept of harm reduction, to actually offer additional other products, aside from cigarettes, that contain nicotine but are much safer to use, such as smokeless tobacco, e-type cigarettes, NRTs."

Sounds pretty much like the strategy adopted 40 years ago (Exhibit 1633) which was looking for a "consumer-oriented strategy for resolution of the smoking-health problem." and to "define the gratifications expected or derived from cigarette smoking and to devise and market profitable new products away from conventional cigarettes which will provide those same gratifications with no significant hazard to the health of the user."

"We continue to try," said Mr. Gentry.

The Stewardship Philosophy

This philosophy does not preclude the sale of "inherently dangerous" products, he said. Nor did it mean that they could not design cigarettes in ways that increased levels of known chemicals, such as when sorbitol was added to Export A cigarettes even though it likely increased the presence of benzopyrerne by a small degree. He said the scientists had to "weigh off" the various test results and make "a judgment on the weight of evidence."

A post-modern linguist could not have been more interested in the meaning of the phrase "stewardship philosophy" than was Mr. Trudel today. But none of his many examples of previous product designs that involved potential increases to risk prompted an admission by the witness that the stewardship philosophy would preclude their sale.

Still - "Stewardship philosophy!" - It does sound good.

This part of the trial takes a slight pause next week while the action moves to Justice Robert Mongeon's courtroom. On the week of November 18th, the last two in-house witnesses for JTI-Macdonald will appear: - Mr. Robin Robb and Mr. Lance Newman.

This post has been backdated. It was written on November 8, 2013.

The documents are on the web-site maintained by the Plaintiff's lawyers. To access them, it is necessary to gain entry to the web-site. Fortunately, this is easy to do.

Step 1: Click on: https://tobacco.asp.visard.ca

Step 2: Click on the blue bar on the splash-page "Acces direct a l'information/direct access to information" You will then be taken to the document data base.

Step 3: Return to this blog - and click on any links.